|

By Kay Shaw Nelson

email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

Sir Walter Scott, one of the

most prolific beloved writers of all time, author of many notable novels and

narrative poems, was also a social historian who had a keen interest in

Scotland’s food and gastronomic traditions. Early in the 19th

century, there was a notable renaissance in Edinburgh and the Lowlands of

old Scots’ dishes and dining customs that were looked upon with new respect,

and “The Whole World’s Darling” did a great deal to foster and promote the

revival of Scottish self-awareness and make people proud once again to be

Scots. It has been said that if ever a man was a publicity agent for

Scotland, it was Scott.

While some persons may consider the gastronomic world of Scots to be of

trifling importance, it is interesting to consider a few references in his

notable works in which the acclaimed author welded the Highland and Lowland

culinary traditions to achieve a heightened awareness of the past and make

the rest of the world take notice. He gave us a wealth of valuable and

fascinating information for food historians and devotees of Scottish

gastronomic lore.

Scott’s tastes in food were said to be plain and Scottish, and he maintained

a lively interest in foods that were grown in his country, regional fare,

and is known to have enjoyed the conviviality of fine dining in his home, at

clubs, and while traveling. “The Wizard of the North” was familiar with the

kitchens of royalty, aristocrats, and crofters.

Revered as “probably the greatest storyteller that Scotland ever produced,”

in his tales of adventure and intrigue with colorful characters and great

descriptions of everyday life and special occasions, Scott was a marvel at

depicting Scottish manners, dialect, and persons of note being those with

which the author was most intimately and familiarly acquainted. Through his

professional studies, Scottish history, antiquity, and walking expeditions

into the Highlands and the Borders Country, Scott acquired an immense

knowledge of local legends, people and their daily lives that went into the

writing of his ballads and novels.

In

1824 Scott wrote that he only ate twice a day – a “bountiful” breakfast and

a “very moderate” dinner. In his novels we can easily trace the evolution of

the Scottish breakfast that has been acclaimed as one of Scotland’s most

notable repasts and one that Scott fondly extols in detail.

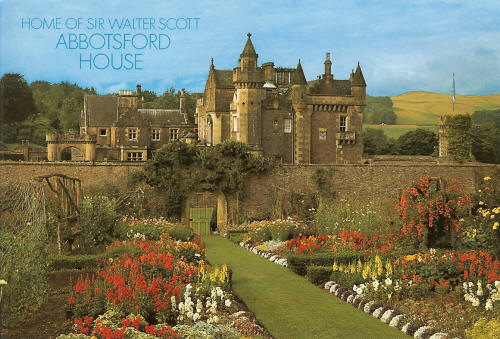

At

Abbotsford House in the Borders where the author lived the life of a country

magistrate and the landowner, his breakfast, served about nine, is said to

have comprised porridge with cream, “salmon, fresh or kippered,” “a

home-made ham, a pie, or a cold sheep’s head,” followed by “oatcakes, or

slices of brown bread spread thick with butter.”

In

Old Morality (1816), Scott’s truest historical novel, there is an

inviting description of a feudal morning meal.

“The breakfast of Lady Margaret Bellenden no more resembled a modern

dejeuner, than the great stone hall at Tillietudlem could brook

comparison with a modern drawing-room. No tea, no coffee, no variety of

rolls, but solid and substantial viands – the priestly ham, the knightly

sirloin, the noble baron of beef, the princely venison pasty; while silver

flagons, saved with difficulty from the claws of Covenanters, now mantled,

some with ale, some with mead, and some with generous wine of various

qualities and descriptions.”

In

Waverley, Scott’s first novel, published anonymously in 1814 and the

first book of The Waverley Novels consisting of thirty-two tales, we

find two descriptions of the eighteenth century Highland breakfast, of

diverse types.

Scott Monument from Princes Street Gardens in

Edinburgh

“Waverley found Miss Bradwardine presiding over the tea and coffee, the

table loaded with warm bread, both of flour, oatmeal, and barley-meal, in

the shape of loaves, cakes, biscuits, and other varieties, together with

eggs, reindeer ham, mutton and beef ditto, smoked salmon, marmalade, and all

the other delicacies which induced even Johnson himself to extol the luxury

of a Scotch breakfast above all other countries. A mess of oatmeal porridge,

flanked by a silver jug, which held an equal mixture of cream and

buttermilk, was placed for the Baron’s share of this repast.”

Then there is an outdoor breakfast where Waverley found himself.

“Much nearer to the mouth of the cave he heard the notes of a lively Gaelic

song, guided by which, in a sunny recess shaded by a glittering birch-tree,

and carpeted with a bank of firm white sand, he found the damsel of the

caravan, whose lay had already reached him, busy, to the best of her power,

in arranging to advantage a morning repast of milk, eggs, barley bread,

fresh butter and honeycomb…To this she now added a few bunches of

cranberries.”

Dining and drinking are aptly described in Scott’s novels. In Waverley

a chapter entitled “The Banquet” we read how the colorful participants

dined.

“The entertainment was ample and handsome, according the Scotch ideas of the

period, and the guests did great honour to it. The Baron ate like a famished

soldier, the Laird of Balmawhapple like a sportsman, Bullsegg of

Killancureit like a farmer, Waverley himself like a traveller, and Bailie

Macwheeble like all four together.” “When the dinner was removed, the Baron

announced the health of the King, politely leaving to the consciences of the

guests to drink to the sovereign de facto or de jure, as their politics

inclined.”

In

Old Morality, a dinner for a laird and his domestics who

partook of some of the fare included “an immense charger of broth, thickened

with oatmeal and colewort, in which ocean of liquid were indistinctly

discovered, by close observers, two or three short ribs of lean mutton

sailing to and fro. Two huge baskets, one of bread made of barley and of

pease, and one of oat-cakes, flanked this steaming dish…The large black

jack, filled with very small beer of Milnwood’s own brewing, was allowed to

the company at discretion, as were the bannocks, cakes and broth; but the

mutton was reserved for the heads of the family…A measure of ale…was set

apart in a silver tankard for their exclusive use. A huge kebbock (a cheese)

and a jar of salt butter, were in common to the company.”

Portrait of Scott by Sir Henry Raeburn

Scott has many references to the Highland fondness for meat, especially

steaks. When curiosity entices Waverley to make an expedition to a den of

robbers and was received with gracious hospitality, he marvels at the

voracity with which they devour the meat. “Steaks, roasted on the coals,

were supplied in liberal abundance, and disappeared…with a promptitude that

seemed like magic, and astonished Waverley.” He is to experience more feasts

and adventures before the actions of the plot are resolved.

In

A Legend of Montrose (1819), involving a conflict in the Highlands

during the Civil War, there is a description of a Captain who “bent his

whole soul upon assaulting a huge piece of beef, which smoked at the nether

end of the table.” And at a dinner for Gentlemens with lighted candles two

English strangers are treated to “an unexpected display.” “The large oaken

table was spread with substantial joints of meat, and seats were placed in

order for the guests.” But elsewhere we read that a “clumsy oaken table” was

spread with milk, butter, goat-milk cheese, a flagon of beer, and a flask of

usquebae.”

Rob Roy (1817), a rousing tale of skullduggery and highway robbery, and

dramatic episodes, has a vivid meal description.

“At

dinner, which we took about noon, at a miserable alehouse,” the men enjoyed

the produce of the hunters “in the shape of some broiled moor game a dish

which gallantly eked out the ewe-milk cheese, dried salmon and oaten

bread…Some very indifferent two-penny ale, and a glass of excellent brandy,

crowned the repast.”

At

another repast a landlady prepare some victuals “…in the frying pan, a

savoury mess of venison collops, which she dressed in a manner that might

well satisfy hungry men, if not epicures. In the meantime the brandy was

placed on the table, to which the Highlanders, however partial to their

native strong water, showed no objection, but much the contrary.”

In

Guy Mannering (1815), revolving around a historical event and notable

for its colorful characters, we read about a hearty game stew. “It was, in

fact, the savour of a goodly stew, composed of fowls, hares, partridges and

moor-game, boiled in a large mess with potatoes, onions, and leeks, and from

the size of the cauldron, appeared to be prepared for half a dozen people at

least,” cooked by a gypsy girl, Meg Merrilies who, we learn elsewhere, likes

her “tass of brandy”.

The

Antiquary

(1816), reputed to be Scott’s favorite among his novels, is a historical

tale “embracing the last ten years of the eighteenth century,” in which

Powsowdie, sheep’s head broth, made with the head and trotters, vegetables,

and barley, is mentioned. And in St. Ronan’s Well (1823), there are

recipes for haggis including cockscombs and deer’s tongues.

Statue of Scott within the Scott Monument on

Princes Street in Edinburgh.

As

for pork, in The Fortunes of Nigel, Scott reminds the reader that

“the Scots, till within the last generation, disliked swine’s flesh as an

article of food as much as the Highlanders do at present.”

Scott has several references to fish, and in The Antiquary his Maggie

Mucklebackit is haggling over haddocks and whitings, bannock-flutes (turbot)

and cockpadles (lump fish), with Jonathan Oldbuck.

While visiting the Northern Isles in 1814, Scott wrote in his diary that

Shetlanders “would not touch skate” and said dog-fish “is only for Orkney

men.”

Scott did not agree that salmon should be served with a sauce. For he wrote:

“The most judicious gastronomes eat no more sauce than a spoonful of the

water in which the salmon has been boiled, together with a little pepper and

vinegar.”

As

for herring he stated, “It’s nae fish ye’re buying, it’s men’s lives.”

In

Heart of Midlothian (1818), there is an interesting comment about

Dunlop cheese. A Midlothian lass, Jeanie Deans, boasts about her skill in

making cheese saying “we have been thought so particular in making cheese

that some folk think it as gude as the real Dunlop.”

Rob

Roy

mentions nettles and describes how Andrew Service, the old gardener of Loch

Leven, raised them under glasses to make an early spring nutritious soup

featuring the herbs.

In

his novel The Bride of Lammermoor, Scott describes a dinner with

desserts that were “a fairy feast of cream, jellies, strawberries,

almond-cream, and lemon cream.”

In

his book, Sir Walter Scott, Edward Wagenknecht writes that

entertainments at Abbotsford were lavish, with great festivals at hunts,

harvest home, and Christmas. A menu he includes is indeed bountiful:

“A

baron of beef roasted, at the foot of the table, a salted round at the head,

while tureens of hare soup, hotchpotch, and cockey-leekie extended down the

centre, and such light articles as geese, turkeys, entire suckling pigs, a

singed sheep’s head, and the unfailing haggis, were set forth by way of side

dishes. Blackhawk and moorfowl, hundreds of snipe, black puddings, and

pyramids of pancakes formed the second course. Ale was the favorite beverage

during dinner, but there was plenty of port and sherry for those whose

stomach they suited. The quaighs of Glenlivet were filled brimful, and

tossed off as if they were water.”

Kenilworth (1821), a tale of 16th century England that draws

on Scott’s familiarity with the Elizabethan age, offers vivid descriptions

of the lavish revels held to entertain royalty. A special point is made of

Queen Elizabeth’s dislike of “all coarse meats, evil smells, and strong

wines.”

Scottish dishes were popularized in court circles. “Nobody among those brave

English cooks,” says Laurie Linklater in The Fortunes of Nigel,

“can kittle up his Majesty’s most sacred palate with our own gutsy Scottish

dishes. So I e’en betook myself to the craft, and concocted a mess of

Friar’s Chicken for the soup, and a savoury hachis, that made the whole

cabal coup the crans (to go to wreck and ruin).”

One

of Scott’s most memorable lines in his fiction comes from this book: “And my

lords and lieges, let us all to dinner, for the cockie-leekie is a-cooling.”

In

the same book more Scots dishes are featured.

“For the cheer, my Lord, a mess of white broth, a fat capon, well larded, a

dishe of beef collops for auld Scotland’s sake, and it may be a cup of right

old wine…”

Clod, a kind of course brown wheaten bread used in Selkirk, leavened and

surrounded with a thick crust, is mentioned by Scott in Redgauntlet

(1824) and is said to have been one of his favorite breads.

Of

utmost significance, Scott is believed to have been instrumental in the

publication of one of Scotland’s most important culinary works, The Cook

and Housewife’s Manual, or Meg Dods’ Cookery, as it was commonly known.

It was published in Edinburgh in 1826 under the pseudonym of Mistress

Margaret Dods.

The

name Margaret or Meg Dods was taken from that of Scott’s impulsive and

eccentric innkeeper character in his fictitious novel of social life, St.

Ronan’s Well (1823), but she is said to have been modeled on Miss Marian

Ritchie, the landlady of his local inn, the Cross Keys in Pebbles. In the

book Meg sets up and runs the Cleikum Club, an institution established to

foster high quality Scottish food and drink.

The manual was actually complied and written by Mrs. Isobel

Christian Johnstone, an author of some note and wife of an Edinburgh

publisher. The humorous and often incomprehensible introduction, a dialog

between gastronomes who plan the Club, is so clever that it is thought to

have been written by Scott. In the zany framework, punctuated by Scottish

comments and gastronomic philosophy as well as domestic advice and household

hints, are hundreds of marvelous exact recipes, many of them with strange

footnotes. Whether or not Scott was the author remains a mystery but the

book has a great deal of literary merit and is valuable by the authoritative

remarks.

Mrs. Johnstone’s greatest contribution to Scotland, however, has been to

provide a written record of its culinary traditions, customs and national

dishes. Many of the old dishes with imaginative names include Inky Pinky,

Cabbie Claw, Venison Collops, Frair’s Chicken, Bashed Neeps, Cock-A-Leekie,

Stoved Chicken, and Howtowdie, among others.

Statues of both Robert Burns and Scott in

Glasgow's George Square.

Note the height of the Scott statue towering over that of Burns.

Although later editions of the manual contained over twelve hundred recipes

covering several cuisines, the importance of the book is the section on

Scotch national dishes. All Scottish cookbooks since then, including modern

volumes, owe a debt of gratitude to Mrs. Johnstone and Scott.

During Scotland’s Age of Enlightenment supper became the really important

meal to promote good conversation and conviviality, and Edinburgh suppers

became a byword. Many took place in taverns and the all-male events for men

of like tastes and opinions thus came into clubs, some with strange names

and customs. One of them, the Poker Club, to “poke up” resentment against

England’s treatment of Scotland, included among its founder members Adam

Ferguson and David Hume, and among the last of the aging members in the

1820s was Sir Walter Scott.

It is my firm determination to re-read some of

Scott’s books for The Epicurean Scot has left us a marvelous heritage of

memorable meals and good times. I have only begun to appreciate some of

them. (KSN: 1-09-08) |